“I had wanted to play with Taako’s sexuality … not in a way that was like, particularly prominent in the story, but, in my mind, when I was doing the character and had Taako’s story in my head, Taako was a gay guy. And I don’t know why, that’s just how it always seemed to me.”

—Justin McElroy, The The Adventure Zone Zone 2016

On The Adventure Zone—a Dungeons & Dragons podcast created by the McElroy brothers of My Brother My Brother and Me podcast fame—Justin McElroy plays as the fan favourite Taako, an elf wizard/chef of immense power that’s, “good out here.”

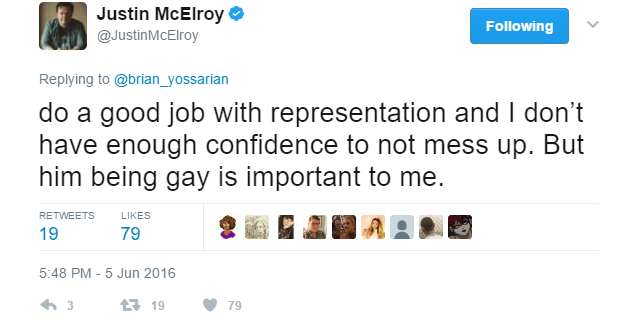

In canon, Taako is gay. IRL, Justin identifies as straight. This is a fundamental lived experience that Justin the person does not share with Justin the character (“Taako”).*

NOTE: I am taking a huge jump into assumption here. I don’t know Justin McElroy personally—he may, in fact, have a lived experience he shares with Taako. I’m not going to presume to say I know his full story. So if I’ve made a horrible error, let me just say, “Hey Justin—I’m sorry. (Also, hi, thanks for reading my article; I love your work!)”

Thus we come to my question: is it okay for a storyteller to create a character with a different lived experience than their own? Whether that’s sexuality, gender, race, creed, social-economic status, and so forth.

My lived experience is a middle-class, fairly WASP-y centric lensed one. What the hell can I possibly know about someone’s experience outside of that perspective? If I were to create a gay character, am I being a positive ally to the LGBTQ* community by creating a character that people can see themselves in? Or am I potentially doing harm by misrepresenting / appropriating a lived experience?

I had a conversation with Amanda a while back. We were talking about this idea of creating characters different than ourselves, and she said something I thought was really profound (I’m paraphrasing her here):

“You should absolutely have characters unlike you. Gender, race, religion—whatever lived experience you don’t have. What you shouldn’t do is then try and make your story about that lived experience. Go ahead, create a female character. But being a man, don’t try and put that character through the ‘female experience’—because you don’t have it. You want to see how your character responds to loss or fulfillment, greed or technology; learning they can throw giant fireballs from their fingertips—do it! Those experiences are as available to you as they are to any of us. But if your character’s core arc is about womanhood when you are not a woman, your story will at best be awkwardly false and at worst outright offensive.”

I sat back stunned aftewards; that idea just made so much sense to me. You can create characters unlike you, but don’t make your story about their lived experience if you (the creator) don’t share it. This method doesn’t prevent storytellers from creating a diverse array of characters through which people can see themselves represented, but it does provide a benchmark by which we can hold ourselves accountable.

Now, there are definitely some hurdles to consider before accepting this idea as “Right Pillar-able”; I consider this merely the start of a conversation on the matter. Before I dive into the first hurdle I see, I’d like to share my experience reading about Kamala Khan (which I think will explain why Amanda’s idea made so much sense to me).

Kamala Khan—the fan favourite Ms Marvel, written by G. Willow Wilson—is a Muslim teen girl from New Jersey. Many of her lived experiences are very different than my own, and yet… I connected more with her as a character than I ever did to Steve Rogers, Tony Stark, or Bruce Banner. Kamala is awkward, funny, and a total geek. She loves her family, but feels they just don’t get her (and kinda overlooks the fact that she doesn’t “get” them yet, either). She’s struggling her way through being a superhero, high school, teenage romance, and has a total hero crush on Carol Danvers, aka Captain Marvel (the original Ms Marvel). Despite our differences, these are all character traits that I totally get because I lived them, too. I may not share Kamala’s religion or culture, but when I see her arguing with her parents over curfews, the reason for the curfew doesn’t really matter—the moment is about the interpersonal relationships of a family. I think most people can share that, one way or another.

I want to tell stories with characters like Kamala; characters that everyone can relate to. Which isn’t to say everyone relates to her in the same way I do. There are plenty of people that don’t connect with Kamala’s geekiness. What I imagine is that they do connect to her because of her relationships, her teenagehood, her humour. That’s why I think Kamala is beloved; there’s so much there that, even if you don’t connect with one piece, there are two or more that you do. She’s struggling through experiences we’ve all faced in our lives, and we love her for it. (Which is the same reason I think Spider-Man is so popular. Spider powers are cool, but it’s his human qualities that make him interesting and relatable.)

Which brings us back around to the topic at hand: representation in stories. Ideally, as an audience you’ll connect to a 3-dimensional character through their humanity, actions, and growth (i.e. Kamala), regardless of their most easily visible traits. That doesn’t mean, however, that these traits aren’t important because they absolutely are. Representation matters. This is where my lived experience is extremely privileged. As a white, heterosexual, cis-gender male, I see myself represented everywhere, where many people (e.g. equity seeking groups) do not (especially in mainstream Western culture). This story from Whoopi Goldberg is a great example of how basic representation (i.e. seeing someone like you) can inspire:

I want to tell good stories and I intend to be a positive influence and a good ally in our world. I feel that part of that means creating spaces for my audience to see themselves in the characters I create. Ideally, they’ll connect deeply with all my characters because of their universal-human traits (as I do with Kamala)—but the fact remains that basic representation matters. Which means I want/need to tell stories with characters of different backgrounds, skin tones, and religions, because putting these characters into art is important—but I don’t want to do so in a way that’s problematic or misrepresentational.

Which means reconciling two needs: to create diverse characters in my work while avoiding any story that I do not have the lived-experience to tell. But is it possible to separate a character’s representation from their universal-human experiences, and even if it is, should it be done? Even if I focus the story on their universal-human experiences, inevitably their representational self becomes woven into that story because those character’s traits will have an important role to play on who the character is and how they interact with their world, conflicts, and other characters.

So—what can I/we do? Only tell stories about characters that look, and act, and are like ourselves? That sounds horrible, and frankly, not helpful to making our art more diverse and intersectional. If I were given a chance to tell a story about Kamala, I would have to focus heavily on her superhero or high school life, with her heritage still there but taking a back seat; I just don’t have the lived experience to be able to tell it right.

Still, I can’t just ignore her heritage (or any character’s representational traits); they’re a part of who she is and, more importantly, affect how she engages in her world. So how do I engage with this part of the character without claiming to have the authority to tell this story/lived experience; to not cause harm by potentially appropriating or misrepresenting?

Well, I’d say some due diligence is in order. This is where listening to friends / colleagues / strangers that do have this lived experience becomes all the more important. I truly believe the best work I’ve done has been collaborative, and collaboration comes in many forms. Listening to people, learning from them, using what they teach to make rich characters—this makes me a better writer, a better storyteller. One, I hope, able to do justice to a character different than myself.

So long as we, as storytellers, ensure that we are conscious of our own lived experiences and the stories we’re trying to tell—and seek help, or, perhaps, abandon a story when we’ve strayed too far from our own experience into someone else’s—I think we’ll be okay. Because not making the attempt at diversity is far more damning than tripping along the way. I’m going to make some mistakes, sure, but you know what? I think it’s much worse to not have full representation in my stories. Every mistake I make will be an opportunity for conversation, a chance for me to learn more about my fellow humans and become a better writer as I do so.